The events leading to the 'Great Crash of 1929' and the development of the 'SEC' which is considered as most successful of all federal regulatory agencies.

The

Great Depression is often called a ‘defining moment’ in twentieth-century

American history. Since equity markets were booming in the 1920s, the decade is

often referred to as the "Golden 20s." However, a few structural

problems did exist that led to the excess money supply in the market and

eventual recession. A few years after World War I, the global economy was still

reeling from the repercussions of the conflict. In 1929, the world was

surprised by an unexpected stock market crash in the USA. It's a one-of-a-kind,

five-sigma event that happens only once in a lifetime. The most lasting impact

of it was the transformation of the role of government in the economy.

On

the New York Stock Exchange, the Roaring Twenties roared most loudly and most

prolonged. The share market skyrocketed. By September 1929, the Dow Jones

Industrial Average had increased six-fold from 63 in August 1921 to 381 in

September 1929. Economist Irving Fisher in 1929 commented that stock prices

have reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau."

In

the end, the boom turned into a cataclysmic bust. The Dow Jones Industrial

Average fell nearly 13 percent on Black Monday, October 28, 1929. The market

fell nearly 12 percent the next day, Black Tuesday. It had lost almost half its

value by mid-November. Its decline continued through 1932, when it closed at

41.22, its lowest value of the twentieth century, 89 percent below its peak.

After the crash, the Dow did not reach its pre-crash levels until November

1954.

After

the Crash, during Great Depression, the American financial market came under

scrutiny, and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was established. In the

New Deal era of President Roosevelt, James Landis played an essential role in

formulating regulations for Wall Street.

In

this review article, I will analyze the events that led to the Great Crash of

1929 and examine James Landis’s contribution in the initial years of the

Securities and Exchange Commission.

The BOOM Period: 1919-1929

In

1919, the USA emerged victorious from World War I. A mood of optimism was in

the air. Britain and its allies were exhausted financially from the wrath of

the war. However, the U.S. economy was thriving. The uncertainties were over. Everyday

life was changing in the 1920s, and electrification, modern

technologies was transforming America. New technologies were coming up –

airplanes, radios, cars, domestic goods that were luxuries by then started

becoming an everyday part of American life. An era of prosperity seems to have begun.

… Buy Now, Pay Later.

A new consumer culture and

mass consumerism have begun on a scale never seen before. For the first time in

history, the credit market started operating in the mass consumer market.

People started buying things on credit and easy EMIs that they could not afford

otherwise. Demand rises in this new economic era of boundless capitalism, and

the market flourishes. This, in turn, changed the American culture and way of

living, which is now generally referred to as the 'American Dream,' that it is

the birthright of every self-respecting American is bound to be rich.

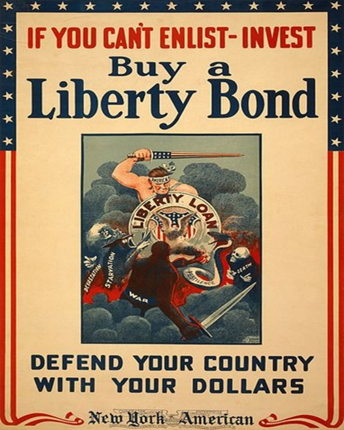

…Liberty Bonds.

Propaganda poster for the Liberty Bond campaign. Via Wikimedia Commons

To help finance the war effort

and give loans to European countries to rebuild after the war, the U.S. Treasury

issued securities termed "Liberty Bonds" in June and October 1917 and

in May and October 1918. Treasury sold large denomination bonds to financial

institutions and bonds with face values as low as $50 directly to individuals.

This attracts first-time investors in the securities market and creates a

culture of investing in ordinary citizens. For the first time, they got

interest payments every six months and could trade the securities. Celebrities

like Charlie Chaplin promoted liberty bonds in massive rallies.

…Charles Mitchell: Wolf of the Wall

Street.

For years, Wall Street, the

center of American finance made up of a small elite group of bankers doing

business with each other in a society closed off to the general public.

However, one man saw an opportunity that changed the face of the financial market

in the world – Charles Mitchell, President of National City Bank. He spotted a

lucrative gap in the market. As people were accustomed to investing with the

introduction of liberty bonds, he thought that all he needed was to market

other investment products like bonds, corporate stocks, and private securities

and convince people that these were good investment opportunities. If people

bought stocks and shares of the companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange,

people like Mitchell could make a profit in the process. This was a very

ambitious dream, but gradually people started investing in stocks breaking the

stigma that stocks are historically risky for ordinary people. The idea took

off, and Mitchell started opening brokerage firms across the country where people

who have the money but not the investment know-how can speculate in stocks and

shares. Share Market became a safe and reliable investment opportunity for the

average American.

…tick tick Ticker Tape.

New technology made the

stock exchange fast in handling this new wave of first-time investors. Ticker

Tape was a machine made with telegraph technology to communicate the stock

prices in real-time. Ticker tapes were all over, from nightclubs, railway

depots to even beauty parlors and sea beaches. The Trans-Lux Company developed

the "movie ticker" in 1923, an illuminated screen that displayed

rapidly changing stock prices. As the ticker tape whizzed by in bright light, a

crowd at a retail brokerage could watch changing stock prices together for the

first time

…Hot stocks… easy money.

People were making easy

money on the stock market. There were wild speculations on all kinds of securities;

from movie companies to aeronautical and automobiles, almost every share was

flying high in Wall Street. Some of the hottest stocks of that time were Radio

Corporation of America, Coca-Cola, U.S. Steel, and General Motors. Everyone

covered the share market through radio shows, magazines, newspapers,

periodicals. People were fascinated to know what stocks the celebrities were

speculating. Even the professional share brokers were also becoming

celebrities. People were following them, eager to know where they were

investing. From the wealthy doctor to the shoe polish boy, almost everyone

invested their life savings in the share market.

One of the exciting

features of the boom period was the participation of women in the share market.

Up until the 1920s, women were not involved in the stock market, partly because

of gender prejudice. It was a common belief that they could not handle the

cruel ups and downs and clever tactics of Wall Street. However, with the

popularisation of the stock market, many women started investing in stocks.

Partly because the 1920s were considered a new chapter in the American feminist

movement; ladies were stepping out, going to college, and eventually taking

care of their own money

…buying share on credit.

The "buy now, pay

later" tool was now introduced in the stock market. A buyer needed only to

provide a fraction of the required funds, borrow the rest, and enjoy the entire

capital gain less the interest on the borrowed funds. Many economic historians

believe that stock market credit was a crucial element in generating the mania

around the share market. Almost 40 cents of every dollar lent in America was

used to purchase stocks, typically through margin purchases

It is easy to understand

the presumption that a credit expansion fuelled the stock market boom by

looking at Figure 2. Because of the tight money policy of the Federal Reserve,

regular credit on the market was low, but brokerage firms circulated credit in

the stock market due to no tight regulation. Due to the easy credit, the demand

for stocks and shares increased, and in turn, the stock prices reached a record

high

…

Laissez-Faire, devil may care.

Throughout the booming

period, the Republican Party stayed in power on the back of America’s boundless

prosperity. Calvin Coolidge became president in 1923. He was an investor

himself and notably silent on the speculative mania of the stock market. He

believed in the laissez-faire economy and is famous for saying that the

business of America is business. As the economy was flourishing, no one

questioned the non-interventionist nature of the government

Moreover, the president and

top government officials were in close connection with the inner circle of wall

street, giving the elite bankers an immense influence over the government's

financial policy. One of the most influential of these elite bankers were the

bankers of the investment firm, JP Morgan, strategical located opposite of the

New York Stock Exchange. They played an essential role in the working of the

market and the devastating events to come. There were rampant market

manipulation and speculation by amateur investors with no disclosure to the

government—millions of people invested in a market where the government had no

laws and regulations.

…Insider trading.

Bankers, corporate

leaders, and financiers created secret investment "pools" to purchase

shares in glamour corporations like American Telephone and Telegraph (AT &

T) during this time. They then sent bank salespeople out to encourage

clients to purchase stocks on margin in the same company. Sometimes phoney

stories were planted in the press, implying that there were "hot

stocks" to buy. This practice was called "insider trading" and somewhat

legally allowed for gross market manipulation. After a relatively short period,

pool members quietly sold their holdings at inflated rates. When the prices

began to settle down to a more realistic level reflecting the company's actual

earnings power and potential, smaller investors who were not a part of the pool

were left holding the bag and owing large sums of money

…confident outside, skeptical inside:

Harbert Hoover

In March of 1929, Harbert

Hoover of the Republican Party took oath as the president of the USA. In his

inaugural speech, he said, "In the large view, we have reached a higher

degree of comfort and security than ever existed before in the history of the

world"

…the warning: Paul Warburg

In the summer of 1929,

prominent investment banker Paul Warburg issued a warning regarding the bubble

created in the bull market. He stated, “If the orgy of 'unrestrained

speculation' in the stock market does not stop, it will 'bring about a general

depression involving the whole country." However, his comments were

dismissed, and he was even accused of not understanding the changes in the

economy

… the bubble is getting even bigger.

Warburg's prediction fell

on defiance, and between May and September 1929, 60 new companies were listed

on the New York Stock Exchange, adding more than 100 million shares in the

market, fuelling the investment bubble. On September 3, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial

Average reached 381.2

…cause for concern?

Harbert Hoover, the President,

was concerned about the bubble and asked around his friends of wall street if

the situation was of any concern? He then received a memo from the senior

partner of JP Morgan, "there is nothing in the present situation to

suggest that the normal economic forces ... are not still operative and

adequate." Yale Economist Irving Fisher publicly announced that

"stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high

plateau"

However, Hoover still did not

intervene in the situation. He still believed in self-regulation and the

independent operation of Wall Street. This is clear from his correspondence

with the elites of Wall Street. There was also no clear understanding of who should

regulate the stock market. This can be clear from one of his own writings.

via

Memoirs of Herbert Hoover

The Great Crash: October 1929

Unlike other market

disasters, the Great Crash was a series of events that occurred over the course

of a week, from Wednesday, October 23, to Thursday, October 31. During these

eight frantic sessions, a total of nearly 70.8 million shares were traded-more

than had changed hands in any month prior to March 1928

…Wednesday, October 23, 1929

The great crash started. No

one knows the sudden loss of confidence at the end of Wednesday, October 23.

Out of nowhere, a sharp loss in the automobile stocks provoked a frantic last hour’s

trading. Millions of shares suddenly sold. The industrials dropped 31 points on

that day

…Thursday, October 24, 1929

Black Thursday is often

considered to be the beginning of the crash. When trading opened on Thursday,

October 24, the Dow fell 11% in the first few hours. That day, a tremendous

fall in the stock prices kept people in shock and utter disbelief. A large

crowd was gathering in front of the New York Stock Exchange with a strange murmuring

humming in the air. The Dow Jones index fell by 12.8%

As the general principle of

economics says, good and evil start falling together when people lose

confidence in the economy. On that day, the wolf himself, Charles Mitchell, who

started all this in the first place, fixed a meeting with the partners of the JP

Morgan and other elite bankers. The public outcome of the meeting was that

Richard Whitney, the vice president of the New York Stock Exchange, went onto

the exchange floor and made bids aimed at stabilizing the market. The first

one, a $205-per-share bid for 10,000 shares of U.S. Steel, is one of the most

well-remembered moments in New York market history. Despite selling orders

continuing to flow in the afternoon, the DJIA closed the day at 299.47, or a

loss of only 1.78 percent

The idea worked, suddenly

all the blue-chip stock prices were rising, and the speculators hoped that the

confidence was back again. A record 12,894,650 shares were traded on the New

York Stock Exchange. Thomas Lamont of JP Morgan held a press conference and

reassured the public that there was no cause to worry

…Friday,

Saturday & Sunday, October 25th, 26th & 27th,

1929

The late transactions on

the 24th were so huge in numbers that the ticker tape machine and

the accountants and bookkeepers of Wall Street were falling behind. They worked

all night to keep track of the transactions, but it took till noon of the 25th

to complete the task

…Monday, October 28, 1929

On Monday, the stock

tickers running out of tape, panicking investors were desperate about the fate

of their share prices jammed the telephone lines between New York and other

major cities. Now, many speculators were concerned about the share bought on

easy credit. The problem with stocks bought on credit was that the falling

share prices could disassemble the entire banking machinery. As the collateral

of these loans was the stocks themselves; creditors were concerned that the

loans might not be paid back with the soaring prices. People got mails from the

creditors to bring more cash, as they needed more collateral. If people could

not pay the additional cash, the creditors warned them that they would sell

their shares to recover money. The market began to fall more steeply, and it

was the worst day in Wall Street history until then. Stocks

again went down on Monday, October 28. There were 9,212,800 shares traded

(3,000,000 in the final hour)

…Tuesday, October 29, 1929

On Black Tuesday, tremendous

waves of selling were just kept coming. Some of the famous names of corporate

America saw their share prices plummet – Radio Corporation of America, General

Motors, U.S. Steel, stocks that have been the symbol of the boom years kept

falling. This time the selling of the stocks was so massive that there was no chance

of any meeting of the bankers at JP Morgan. The situation was then entirely out

of hand. The market broke very sharply. The Dow Jones indices fell from 260.64

to 230.07, i.e., a fall of 30.57 points

Dow Jones Industrial Average during the Crash via Value Walk

New York Times on October 30, 1929, via New York Times on Twitter

…Thursday, October 31, 1929

31st regarded

as the last day of the crash. The crash devasted people. There was a great deal

of interest in the psychological effects of the stock market crisis in the

early days. The newspaper commentaries picked up on suicides caused by the

market, like John G. Schwitzgebel of Kansas City, who shot himself in the chest

at the Kansas City Club on October 29

People gathered around New York Stock Exchange via National Geographic.

The aftermath of the Crash

A

third of the U.S. economy fell between 1929 and 1932, from $103.1 billion to

$58.0 billion. To what extent was the stock market collapse responsible for the

collapse? July 1932 marked the Dow's lowest point (40.56 points). The long

decline resulted in a substantial loss of wealth, which affected consumption

immediately. More than $20 billion was lost by investors (sometimes referred to

as 600,000 widows and orphans) after the stock exchange

Many

companies closed their operation after the crash. There was rampant

unemployment in the country. Banks were closing, and as there was no insurance

of the deposits in the bank, people lost their life savings. Unemployment and

homelessness was the face of American cities. There were people living in tiny

houses made up of cardboard; these colonies were called Hooverville.

…Hoover’s Response

In keeping with his

non-interventionist principles, Hoover's response to the crash focused on two

very common American traditions: Asking individuals to work harder and he asked

the business community to voluntarily help sustain the economy by retaining workers

and continuing production. The U.S. president immediately convened a conference

of leading industrialists in Washington, DC, encouraging them to maintain their

current wages during the short economic crisis. He told business executives

that the disaster was not part of a more significant downturn and that they had

nothing to be concerned about. Similar discussions with CEOs from power

companies and railroads resulted in promises of billions of dollars in new

construction projects, while labor leaders agreed to hold off on pay demands

and workers continued to work. In addition, Hoover pushed Congress to pass a

$160 million tax cut to boost American incomes

Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Franklin D Roosevelt was

elected to the presidency four times, serving from March 1933 until he died in

office in April 1945. As president, he started changing the American

administration known as the ‘New Deal, a package of federal legislation. The

New Deal was inspired by a spirit rather than a blueprint for action., as

Roosevelt said, of “bold, persistent experimentation,” in which he would “take

a method and try it: if it fails, admit it frankly and try another.”

He moved fast to safeguard

bank depositors and put a stop to dangerous banking practices. He pushed

through measures in Congress to combat securities fraud. He aided indebted

landowners and farms on the brink of losing their homes and property. In

addition, he attempted to promote inflation in order to support the economy's

declining prices and salaries.

Formation of Securities and Exchange Commission

There has not been another

era of similar crisis and recognized the need for a fundamentally fresh

strategy to financial regulation since 1929-33. Congress established the

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 as the first federal

securities regulator. It is an independent regulatory agency charged with

safeguarding investors, ensuring the fair and orderly operation of securities

markets, and enabling capital formation. The SEC regulates regional stock

exchanges, investment businesses, investment advisers, over-the-counter

markets, corporate reporting activities, accounting practices, and several

specialized disciplines such as public utility holding companies, bankruptcies,

and overseas corrupt practices. The agency had expanded from a modest office of

approximately 150 employees in 1934, when it was founded during the New Deal,

to a vast bureaucracy of about 2000 employees today.

The Securities Act of 1933

(Securities Act) and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Exchange Act), the

laws that had the largest impact on the securities market, were key components

of the regulatory protections put in place during the Depression. The

Securities Act's primary goal is to govern issuers' initial distribution of

securities to public investors. The Act necessitates filing a registration

statement for securities offered through interstate commerce or the mails. The

purpose of registration is to provide complete and accurate information on the

securities offered to the public. The Exchange Act regulates the securities

exchange markets as well as the activities of firms listed on national

securities exchanges (such as the New York and American stock exchanges)

The SEC's success can be

attributed in significant part to the initial approach devised by its founders.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), led by Joseph P. Kennedy, James

M. Landis, and William Douglas, tried to restore public confidence in the

capital markets and persuade regulated interests to assist in the enforcement

of the public policy. The SEC pushed for building private-sector regulatory

frameworks, utilizing its power and influence to promote what became known as

"public use of private interest"

Roosevelt was at the head

of all the policies, but there were two more interesting gentlemen whose

presence made the SEC successful. One was Joseph Kennedy, the investor himself

and, as mentioned earlier, one of the few men who made out the crash without

financial loss. Kennedy was a master manipulator as an investor on Wall Street.

So, he knew all the ways in which bankers and investors in Wall Street

manipulated the market and committed fraud. So there were no other men suitable

to prevent fraud apart from the fraud himself. Another one is the Harvard

fellow James Landis, who later taught the world how to regulate the financial

world.

Conclusion

Men have been swindled by

other men on many occasions. The autumn of 1929 was, perhaps, the first occasion

when men succeeded on a large scale in swindling themselves

Overall, the Great Crash of 1929 had a profound impact on financial regulation in the United States, leading to the creation of the SEC, the expansion of banking regulation, increased transparency, and strengthened enforcement of financial regulations. These reforms helped to restore confidence in the financial markets and prevent similar crashes in the future.

References

Bierman, H. (

2008, March 26). The 1929 Stock Market Crash. Retrieved from EH.net

Encyclopedia: https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-1929-stock-market-crash/

Connon, H. (1999,

October 29). Echoes of Wall Street crash. Retrieved from The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/business/1999/oct/24/columnists.observerbusiness

Ferguson, N.

(2013, June). Is the Business of America Still Business? Retrieved from

Harvard Business Review:

https://hbr.org/2013/06/is-the-business-of-america-still-business

Ferguson, T. (1984).

From Normalcy to New Deal: Industrial Structure, Party Competition, and

American. International Organization, 38(1), 41-94.

Galbraith, J. K.

(2001). The essential Galbraith. houghton mifflin company.

Hayes, A. (2021,

October 12). Black Thursday. Retrieved from Investopedia: Black

Thursday

Hoover, H. (1929,

March 4). Inaugural Address of Herbert Hoover, March 4, 1929. Retrieved

from Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum:

https://www.google.com/search?q=herbert+hoover+inaugural+address&rlz=1C1FKPE_enIN980IN980&sxsrf=AOaemvKxsWBp_a_iLltzoWzys0CkqBi7SQ%3A1640297676277&ei=zPTEYZHEEOWT4-EPnouYwAI&oq=herbert+hoover+inau&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAEYATIFCAAQgAQyBQgAEIAEMgUIABCABDIFCAA

Hoover, H. (1952).

The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover. New York: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Houck, D. W.

(2000). Rhetoric as Currency: Herbert Hoover and the 1929 Stock Market Crash. Rhetoric

and Public Affairs, 3(2), 155-181.

James, H. (2010).

1929: The New York Stock Market Crash. Representations, 110(1),

129-144.

Keller, E. (1988).

Introductory Comment: A Historical Introduction to the Securities Act of 1933

and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Ohio State Law Journal, 329-352.

Kennedy, J.

(1929). Joe Kennedy and Stock Market Crashes. Retrieved from

scheplick.com:

https://scheplick.com/2020/01/27/joe-kennedy-and-stock-market-crashes/

Klein, M. (2001).

The Stock Market Crash of 1929: A Review Article. The Business History Review,

75(2), 325-351.

Klein, M. (2001).

The Stock Market Crash of 1929: A Review Article. The Business History

Review, 75(2), 325-351.

Komai, G. R.,

Alejandro, Gou, M., & Park, D. (2013, November 23). Stock Market Crash

of 1929. Retrieved from Federal Reserve History:

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/stock-market-crash-of-1929#footnote1

Landis, J. (1941).

Mr. Justice Brandeis and the Harvard Law School. Harvard Law Review, 55(2),

184-190.

Landis, J. (1961,

February). The Administrative Process: The Third Decade. American Bar

Association Journal, 47(2).

Latson, J. (2014,

September 3). The Worst Stock Tip in History. Retrieved from Time:

https://time.com/3207128/stock-market-high-1929/

McCraw, T. (1982).

With Consent of the Governed: SEC's Formative Years. Journal of Policy

Analysis and Management, 1(3).

O'Brien, J. (2014,

October 27). Too Big To Fail or Too Hard To Remember: James M. Landis and

Regulatory Design. Retrieved from Centre for Ethics, Harvard University:

https://ethics.harvard.edu/blog/too-big-fail-or-too-hard-remember-james-m-landis-and-regulatory-design

Raskob, J. J.

(1929). Everybody Ought to Be Rich. Ladies' Home Journal, 236-239.

Ritchie, D. A.

(1980). Reforming the Regulatory Process: Why James Landis Changed His Mind. The

Business History Review, 54(3).

Roosevelt, F.

(1932, May 22). Address at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. Retrieved

from Georgia Online: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-oglethorpe-university-atlanta-georgia

S&P_Global.

(1929). dja performance report daily. New York: S&P Global.

Schmidt, J. H.

(2019). The Great Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression in the Global

Context. Faculty Centre for Applied Finance and Banking Working Paper

Series.

sechistorical.org.

(n.d.). 431 Days: Joseph P. Kennedy and the Creation of the SEC (1934-35).

Retrieved from sechistorical.org:

https://www.sechistorical.org/museum/galleries/kennedy/building_a.php

Shiller, R. J.

(2021, April 16). Looking Back at the First Roaring Twenties. Retrieved

from The New York Times:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/business/roaring-twenties-stocks.html

Sutch, R. (2015,

September). Financing the Great War: A Class Tax for the Wealthy,. Berkeley.

Walk, V. (2018,

April 8). A brief history of the 1929 stock market crash. Retrieved

from The Business Insider:

https://www.businessinsider.com/the-stock-market-crash-of-1929-what-you-need-to-know-2018-4?IR=T

White, E. N.

(1990). The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited. The Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 4, 67-83.